This post will obviously have spoilers for Superman. And, less obviously, for the 2006-2012 comic series The Boys...and maybe the 2003-2007 volume of The Outsiders too...

•Overall? I thought it was quite good. It's definitely the best Superman movie I've ever seen in a theater, and maybe the best Superman movie ever (I should note that I didn't actually sit down and watch the Christopher Reeve movies start to finish until I was an adult, and thus have no real nostalgia for those films, although, yeah, Reeve is a fantastic Superman and Clark Kent).

I thought this was the first of all the Superman films that felt like it starred the comic book version of the character, rather than some new or different or original movie version of the character, and it is the first movie I've seen that seemed to be set in some recognizable version of a DC Universe.

I think that bodes well for the future, given that this is the launch of a new (and hopefully improved) DC answer to the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

•The change in approach. I think the most immediately telling difference between James Gunn's Superman and the previous iteration from Zack Snyder's 2013 The Man of Steel and the handful of "DC Extended Universe" films he appeared in is that the Snyder version seemed somewhat insecure and defensive in its very conception.

That is, when Snyder and his studio bosses set out to make a new film version of Superman, a character universally known by his iconic costume, they seemed somewhat embarrassed by that costume's bright colors and the red trunks being worn over blue tights...or, if not embarrassed, than at least worried that such a character might not be taken seriously enough.

Gunn's Superman, on the other hand, not only has a costume featuring his traditionally bright primary colors, and that not only features the trunks, but he's also accompanied by his flying, super-strong dog with a matching cape.

It reminded me of something from a social media post that's stayed with me over the years. I wish I could remember who said it so I could properly credit them [Update: Kevin Hines informs me that it was Brett White, and he shares a screenshot of the original tweet.] It was in reaction to the fact that DC and/or Warner Bros or whoever were once again publicly hemming and hawing about the difficulty in making a Wonder Woman movie, while Marvel Studios was in the midst of advertising the then-upcoming Guardians of the Galaxy (so this would have been circa 2013 or 2014, I guess).

The statement was along the lines of, "DC's like 'We're not sure people will get Wonder Woman', while Marvel's like, 'Here's a raccoon with a machine gun.'"

The raccoon with a machine gun film was, of course, directed by James Gunn.

•The politics I've seen a fair amount of discussion about the politics of the new Superman film reflected on my Bluesky feed, probably a result of the fact that everything I tend to pay attention to online has to do with either comic books or politics. (And I'm not just referring to the silly statement from a particular actor who used to play a TV Superman saying, before he had even seen the movie, that it was somehow wrong or bad that Superman was being depicted as an immigrant...you know, just as he has been for 87 years now.)

Honestly, I think this headline from the Vulture review of the film by Alison Willmore, which I saw here, best captures the political agenda of the film: "Superman Isn't Trying to Be Political. We Just Have Real-Life Supervillains Now."

A relative of mine liked the new Superman film a lot, and, in texting me afterwards, she mentioned two points related to the real world.

First, she said that she got something of an Elon Musk vibe from Lex Luthor. Now, if Luthor reminds you of Musk, or Donald Trump, or any other rich, powerful person making your life worse, well, that's somewhat intentional....at least on the part of DC Comics, if not necessarily James Gunn.

That's because when John Byrne reconceived the entire Superman franchise for DC's emergent post-Crisis continuity in 1986, he purposefully turned Superman's perennial archenemy from a typical supervillain into a rich, powerful businessman/corporate CEO type—a then more relevant, visceral vision of evil than that of a mad scientist or crook in tights. Byrne's new Luthor was the sort of bad guy that hides in plain sight, being more-or-less accepted by society at large while engaged in nefarious acts in secret.

That's just who Luthor is, and has been for some 40 years now.

In the film he is, as expected, also duplicitous and manipulative, driven not only by greed, but also by his envy of Superman and, perhaps, a personal animus against aliens to commit his various bad actions. Again, that's just Lex Luthor being Lex Luthor.

This particular version is also a pretty bad boss (I liked the bit where he yelled at his employees to clean up a mess he made, and then purposefully knocked over a mug holding pencils like a cat as they did so). And a rather shitty boyfriend.

Oh, and he also engages the comic book supervillain equivalent version of using bots to help shape public opinion on social media.

And, as we will learn near the climax, he wants to be a literal king.

If any of that reminds you of the current president, or Elon Musk, or any other real world figure, well, that probably reflects more on that figure's behavior than on any creative decisions Gunn made in his depiction of the Lex Luthor character (I will note a distinction that the above-cited critic, Alison Willmore made between Luthor and our real-world supervillains: Lex Luthor is really smart, while Trump and Musk are famously...not. I would also add that Luthor is, at least in this particular portrayal, also fairly young and rather handsome, and thus makes a poor filmic stand in for the likes of Trump or Musk).

Now, there are two specific points of the film that seem to more directly address real-world events. One I think was probably intentional on Gunn's part, the other is almost certainly a coincidence, and the fact that it's in the film at all is more a matter of unhappy circumstance in the real world than some attempt by Gunn to comment on it. That is, it is, again, more about the us having real supervillains than Gunn trying to make any particular political points.

One major plot point in the film is the invasion of one fictional country by its neighbor, another fictional country. The former, the victim nation, is Jarhanpur, while the latter, the aggressor, is Boravia.

While they both sounded vaguely familiar, I didn't recognize either when I first heard them mentioned, nor did I connect them to any particular DC comics past while I was sitting there in the theater. Looking them up when I got home, I saw that Jarhanpur appeared during Joe Kelly and Doug Mahnke's JLA run, being introduced in the "The Golden Perfect" story arc (fom 2002's #62-#64).

There it was presented as an exotic, fantastical country, but it was, visually, coded to resemble a Middle Eastern, maybe Muslim majority coded country. The people all had brown skin, the buildings had minarets and Plastic Man made joking reference to belly dancers and Ramadan.

As for Boravia, it apparently appeared in a couple of stories in 1939's Superman #2 and 1958's Blackhawk #126. I don't think I've ever read either—I might have read and forgotten the Superman story, while I know I've neve read any Blackhawk comics—but it seems to be, as it sounds, a European country.

Unlikely neighbors, then.

Sometime before the film begins, Superman apparently intervened in Boravia's invasion of Jarhanpur, destroying some of Boravia's military hardware and then flying that country's leader into the dessert to essentially threaten him not to try it again.

I immediately took this to be an intentional parallel to Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February of 2022, thanks, I think, to the geography in play (In the movie, Boravia is immediately east of Jarhanpur, with which it shares a border). That and the rationale the president of the aggressor nation gave for the invasion in a press conference, something about liberating its people from their own fascist government.

A few days after I had seen the film, that relative I mentioned above asked if I thought this aspect might have been a nod to the Israel's war on the Palestinian people in the Gaza strip, launched in 2023 in retaliation to the October 7 terror attack by Hamas. She was not the only one to note this possible reading; I've seen social media posts reading the movie that way, with one noting that the film made Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu one of its villains.

Honestly, this reading didn't occur to me at all as I was in the theater, but, after hearing it, I could certainly see it: The apparent desert climate of the two countries, the fact that Jarhanpur's people seemed to be composed mainly of poor brown-skinned people, the fact that Boravia had a professional military with uniforms and tanks and jets and, at the climax, they line up to attack what looks essentially like a bunch of civilians.

And now that I've picked up some old copies of JLA and see what Jarhanpur looked like in the comics, it certainly seems more like the Middle East than Eastern Europe. (Also, there's the fact that Luthor apparently did a deal with Boravia in which he would get a portion of the conquered land as his own, not unlike Trump expressing his desire for the United States to "own" the Gaza strip once Israel and/or the U.S. managed to quite illegally displace all of the people who live there.)

Was Gunn referencing either—or both—of these conflicts?

Maybe.

Given when these particular crises started, he would have certainly had the lead time to work them into his screenplay.

On the other hand, it could be as simple a matter as Gunn making the rather broad, anodyne and hard to argue with statement that the unprovoked military invasion of a neighboring country is wrong, or, even more broadly, that the strong should not victimize the weak.

I think, a few years ago, all Americans could agree on that, but, when presented with real world examples like the conflicts mentioned above, Americans have various opinions. One imagines that just like so many Republicans in congress and right-wing influencers are either pro-Russia or, at least, ambivalent to the fate of Ukraine, they would similarly be unmoved by the plight of Jarhanpur if they were serving in the DCU's congress or doing their podcasts there.

The other plot point that is echoing real life? Well, it's not exactly subtle.

The alien Superman, who illegally "immigrated" to Earth and lived his whole life as an upstanding American citizen and productive member of society, is, at one point, roughed up by a man in a mask working on the behalf of the U.S. government and then whisked from American soil to a "foreign" forever prison without the benefit of any due process, literally being told that, as an "alien", he has no rights.

That's some evil supervillain shit, obviously, but, given the lead time needed to make a movie of this size and expense, Gunn and his fellow filmmakers had almost certainly written, filmed and had maybe even produced the special effects for those scenes well before masked goons kidnapping immigrants from our streets and putting them in detention facilities or shipping them to foreign countries without any due process was yet a common occurrence in America. (Trump didn't invoke the Alien Enemies Act until March 14 of this year, for example.)

Personally, I think Gunn was just using his imagination to come up with something wicked and un-American to show just how evil Lex Luthor is. He probably wasn't imagining that the Trump administration would be regularly doing that very thing by the time his big, summer film started playing in theaters.

Finally, one of the two most evil things Luthor does, or threatens to do in this film, includes threatening to "euthanize" the perfectly healthy (if often misbehaving) dog Krypto, making a point of telling a helpless Superman that doing so will probably be quite painful for the dog. Meanwhile, here in the real world, the current secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, and thus a person quite high up on the organizational chart when it comes to implementing the policy of snatching up immigrants to send to prisons abroad, is Kristi Noem, a woman who rather famously shot her perfectly healthy dog Cricket to death due to its behavior problems.

Again, Gunn likely wasn't calling Noem out. He was probably just demonstrating that Luthor is evil. So is Noem.

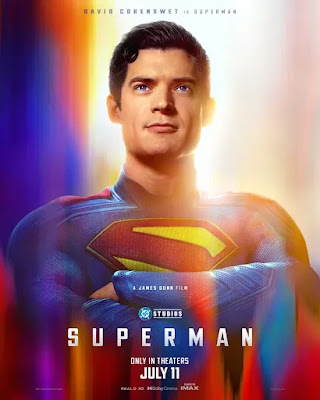

•David Corenswet I thought David Corenswet did a phenomenal job with what turned out to be a fairly complex job. Rather than a simple dual role, in which he had to play Clark Kent and Superman as two entirely different characters, his Superman was conceived in such a way that there were various layers to the character, and to what degree he was being himself in any particular scene.

I found it interesting that, in this particular outing, both Clark Kent and Superman are sorts of public performances that the real character playing them both, who I guess we can call Kal-El for clarity's sake (even though I don't remember that name being used in the film at all), takes on at different points.

We only see that real character behind them both, Kal-El, in a few instances. When starting dinner in Lois' apartment, for example, or when he's recovering from his pocket universe ordeal at his parents' farmhouse in Kansas...and, I suppose, occasionally bleeding into his Superman persona, when he's alone with Lois in front of the "interdimensional imp" battle, or gets angry or frustrated while wearing the suit.

I think this is probably most evident during the interview scene, when he says "Miss Lane," and essentially turns his Superman persona on as if he was flipping a switch. Throughout, as he gets frustrated at some of her questioning, we can see his real, Kal-El self keeps intruding on his Superman performance, too.

It's a rather nuanced performance, far more than the just looking handsome and strong and inspirational and nice that one might expect of a Superman actor.

I do sort of regret that we didn't get to see more of Corenswet's Clark Kent performance in the film, but, I suppose, that needed to be sacrificed in order to give us a version of Superman that has already revealed his secret identity to Lois. Still, with such a big and interesting cast in the Daily Planet scenes, it would have been nice to see more of Clark; maybe in a sequel...?

Corenswet, Gunn and company did a good enough job of making Clak and Superman seem like two entiely different people that it was easy to believe that no one made the connection between the two (I know Guy Gardner references the hypno-glasses, a bit of forgotten Superman lore that I've never actually encountered in a comic book, but then do you want to take Guy Gardner's word for anything...?

•Nicholas Hoult Nicholas Hoult's Lex Luthor was similarly great. It was certainly the best live-action performance of the character that I've ever seen, although I've never seen any of the TV Luthors that weren't animated (I know a lot of folks really like Michael Rosenbaum's Smallville Luthor).

Hoult's Luthor is handsome, quick-witted and charming, and it's easy to see how this Luthor could prove to be charismatic enough to be the leader of a company or sell the U.S. government on his metahuman Planet Watch force (or whatever it was called) or be a popular media figure.

Part of this Luthor's enmity towards Superman seems to be that the hero pulls the world's focus away from Luthor himself, who thinks he should be the center of the world's attention, and Hoult's Luthor is one that we could imagine being that center of attention.

He also, more than any of the previous actors, looks and acts like the Luthor I recognize from the comic books of the last 25 years or so.

•Luthor is so bald And speaking of Luthor, I don't know exactly how they did it, but man, this Luthor is so bald. Like, there is no hair anywhere on his head at all. There are close-up scenes where, on the big screen, you can see Hoult's head filling that gigantic space, and you can see the little roots of hairs left on his clean-shaven face, but his scalp...? Nothing. I don't know if they used a bald cap or, like, digitally removed any and all hairs on his shaven head in post, but Superman's Lex Luthor is, like, the baldest anyone has ever been in a movie.

•It needed more purple and greenThere's a brief shot of a flag at the decommissioned army base by "the river" where Luthor keeps one of his pocket universe portals, the place with all the tents (I am 99% sure that those scenes were filmed at a beach in Mentor, Ohio, where I used to live and still work, and that the river in the back ground is actually Lake Erie). That flag is yellow and green, rather than purple and green. For the life of me, I can't imagine why they didn't go with purple and green in that shot.

Similarly, I wish that Luthor's "Raptors" wore purple and green armor, rather than the kind of generic black/metallic coloring they have. Given the deepness of the cuts in the film—the hypno-glasses, Boravia—I have to imagine the filmmakers at last had a conversation about coloring the Raptors purple and green and must have had some reason not to do so.

•Rachel Brosnahan Rachel Brosnahan is also a particularly strong Lois Lane. She definitely looks the part, and I think she captured the character pretty well. I think because of the fact that we're already past the learning of the secret identity point of the relationship, it frees her up to do more, and be a more active partner in Superman's life, while, at the same time, their relationship is new enough that there is still some drama in it; that is, they haven't yet reached some sort of happily ever after point with one another, where they tend to be in the comics these days, just yet.

I like that we got to see her doing some journalism and we got to see her doing some mild adventuring and we got to see her doing some journalism while doing some adventuring, in that scene at the climax where she's dictating a story while piloting a UFO. That's some quality DCU journalism right there.

•The origins of Krpto I heard an interview with Gunn on NPR last week where he talked about how this particular portrayal of Krypto was inspired by his own experience with a terribly behaved dog.

Still, after seeing the film, I wondered if Gunn had ever read Mark Russell's The Superman Stories. Russell, who admitted that he hadn't really paid any attention to actual Superman comics before writing his prose stories, presents a very different vision of a Superdog, but the gag with Russell's is just how terrifying and what a public menace a dog with all of the powers of Superman would actually be. I thought of Russell's Superdog in the scene where we see that Krypto has broken through the glass storefront of a pet store and helped himself to some dog food, which reminded me of Russell's dog's deprivations.

•Mister Terrific I thought the film made great use of the Mister Terrific character, a really rather minor character in DC Comics history, being a legacy version of an even more minor, footnote of a Golden Age character. He's not a character one might expect to see turn up in a Superman movie, or even a movie dealing with any iteration of a Justice League as opposed to a Justice Society (His appearance in Justice League Unlimited cartoon notwithstanding).

I especially appreciate that they used him instead of Blue Beetle Ted Kord who, given the presence of Guy Gardner and Maxwell Lord, would have been the most obvious candidate for "the smart one" in a "Justice Gang"...especially since Ted came with his own flying vehicle, something so necessary for the film that they had to invent one for Mister Terrific (On the other hand, the old, bad DC Extended Universe produced a Blue Beetle film just two years ago, and, having never seen it, I'm not sure whether or not it had a Ted Kord character in it at all. Anyway, maybe it would have been weird to use another Blue Beetle in this film).

Edi Gathegi's performance as Mister Terrific was, well, terrific. I liked his deadpan delivery, and his ongoing frustrations with his colleague Guy Gardner, Lois and even Superman. His coolness and confidence seemed to be borne of the original conception of the character, as he appeared in that one issue of The Spectre that introduced him, more so than in his later, more popular appearances in various JSA titles.

Gathegi looked a little smaller and less imposing than I would have imagined Michael Holt to be in real life (same with Hawkgirl, actually), but his costume couldn't have looked any better, seemingly pulled directly out of the comics with only the little Max Lord/"Justice Gang" symbol thingee on the chest added. Even that weird mask seemed to work in live-action.

•Most importantly So the line "I'm goddam Mister Terrific"...inspired by All-Star Batman and Robin, The Boy Wonder, or nah...?

•Metamorpho In contrast, I didn't really care for the visual depiction of Metamorpho in the film and, the longer I think about it, I can't help but wonder if he's just a character that doesn't really work in live-action...or, at least, not as well as he does in comics, or the more comic-like medium of animation.

I think actor Anthony Carrigan did a decent enough job in the role, particularly as far as expressing the "freak" nature of the character and Rex Mason's resignation to that nature. He also did a fine job of expressing the rather tough ethical/moral dilemma the film put Rex in, forcing him to decide to inflict violence on a stranger or strangers so that no violence is inflicted upon his own son.

Still, Carrigan is a lot smaller than any of the Metamorphos I've read about, be it Ramona Fradon's original version from the '60s, or Bart Sears' version in Justice League Europe or and those that followed in various Justice League books or crossovers or anthologies.

Additionally, the film's version seems to have elaborate scoring or scarring on his face, suggesting the Metamorpho of the 2003-launched The Outsiders (who actually turned out to only be an aspect of Metamorpho, and took the name "Shift", I guess; retroactive spoiler alert!).

Finally, he looked weird wearing what looked like baggy shorts to, I suppose, protect his modesty. If they didn't want to go with the form-fitting briefs with an "M" on the belt buckle, they could have at least got him some better fitting trunks, akin to those Corenswet's Superman rocked.

Some of the demonstrations of his powers looked kind of cool (growing Kryptonite out of his hand, forming that big hammer in the climax), but others just looked...weird and indecipherable as when he was flying in a half-gaseous state, or when he had tentacles. Again, I think he mainly just isn't a comic book character that translates all that well to live action.

•Green Lantern Speaking of, do Green Lanterns just not work in live action? Nathan Fillion is pretty great as Guy, and as glad as I was that they chose to use that particular Lantern (certainly the best one to choose when it comes to contrasting against Superman's personality or brand of heroics) his powers looked a bit weird and fake to me whenever he used them. His constructs looked more like cheap plastic than hard light. (I thought his powers looked far better when seen from a great distance, as when he and the J.G. are fighting the "imp" in the background, and all we see of Green Lantern are some green flashes, beams and giant baseball bat).

Also, Guy seemed to be able to fly without any sort of aura around him, which isn't how I thought their rings worked, but whatever, I suppose that varies from artists to artist.

Anyway, after this and 2011's Green Lantern, which I don't recall really selling Green Lantern constructs terribly effectively either, I'm left wondering if, like Metamorpho, those characters' powers are ill-suited to being depicted in live action.

•Maybe Neil DeGrasse Tyson will weigh in You know the bit where Superman, Krypto, Joey and Metamorpho are all being dragged toward the black hole in the pocket universe, and Superman uses his super-breath to push them away from it? Would that really work?

I'm asking, as I have no idea.

It felt a little dubious, though, and I woulda preferred if Metamorpho turning into a rocket would have been all that was necessary to free them, as that seems a bit more cut and dry and, well, um "believable" (You know, in a scene involving a flying dog in a cape and a guy who can turn himself into a rocket).

•Another deep cut? I like that they included a scene involving what was essentially the old Daily Planet flying newsroom, when Perry orders the staff onto Mister Terrific's ship, where they can finish up the Luthor expose while flying through the air, as the city is imperiled by the dimensional breach.

•But enough about DC Comics I wonder if the Ultraman reveal has any impact on The Boys, either the show, which has yet to wrap up, or the comic book which, while years old at this point, is probably going to still keep being new for some readers...many of whom, in the future, will likely have seen Superman before reading.

I thought the reveal of what Ultraman looked like under his mask was spectacularly obvious, based on his costume alone (so I've been expecting it for months now) and, wow, they sure telegraphed it by the scene relatively early in the film where the Fortress opened up to allow Luthor, Ultraman and The Engineer entrance.

Anyway, that Ultraman costume looked a fair bit like Black Noir's comic book costume and, if you've already read The Boys, then you know the way in which Ultraman's relationship to Superman is similar to Black Noir's relationship to Homelander, The Boys' version of Superman.

I've never watched the TV show, but, from what I've heard, the showrunners were planning on going in a different direction at the end than Garth Ennis and company did in the comic (it sounds awfully different in general, really), and thus I imagine that one particular reveal will play out different.

For the folks making the show and the audience enjoying it, I hope that's the case at this point; it would be too bad if the new Superman movie inadvertently spoiled the ends of The Boys TV show.

•The fates of the non-Luthor villains Finally, while I'm not entirely sure how it could have been done differently, I was a bit disappointed that both Ultraman and the Boravian leader seemingly died at the end of the film.

This is, of course, in large part because of how sour the ending of the Man of Steel was, in which Superman took the life of his opponent, perhaps the most un-Supermanly thing he could have done in a film.

Gunn certainly seemed to telegraph early and often that that's not his Superman, as he not only spent a lot of time saving people and even checking on them to make sure they were alright, but he also took pains to save a random barking dog and a squirrel, and expressed frustration with the Justice Gang for killing a giant monster threatening the city, rather than finding a non-lethal solution to the problem. And, of course, the motivation for some of Superman's actions in the movie are his concerns for a dog, Krypto.

The point was hard to miss: Superman not only cares about human life, he cares about all life.

So while the killing off of Ultraman is somewhat ambiguous, with Superman kinda sorta knocking him into a black hole and not saving him, it still seemed somewhat out-of-character for this Superman. I kind of wish either Superman managed to save him and turn him into a friend off-screen, and we got a shot of a happy Ultraman in the Fortress at the end, or, even more simply, they had given Lex a line or two in which he states that Ultraman technically isn't even alive, but is some sort of biological automaton or something.

That said, if a future movie has Ultraman come out of a blackhole with chalk-white skin, wearing a homemade Superman costume and talking backwards, well then, I'm totally fine with it.

As for the Boravian leader, Hawkgirl seemingly drops him to his death, a moment meant to draw another sharp contrast between Superman and the Justice Gang's brand of justice. It seems awfully harsh—especially if we're meant to see him as a stand-in for Vladimir Putin or Benjamin Netanyahu—and given what a big deal Superman's intervention in Boravia's invasion plan was in the world of the movie, well, the assassination of its leader seems like a much, much bigger deal, no?

Given that Gunn thinks it's important to explain why Krypto is such a poorly behaved dog during that surprise cameo at the end—surely Superman could properly train a dog—his lack of explanation regarding the deaths of Ultraman and, maybe, that of the Boravian leader felt a bit jarring.